The Rewiring of Local News

A Civic Conversation with Abby Tegnelia

February 16, 2026

Something fundamental is shifting in Saratoga. It has less to do with any single publication than with the architecture of how a community knows itself.

For generations, the local newspaper functioned as a civic hearth. It was not simply a delivery system for information but a shared mental map — the place where residents discovered what mattered, who mattered, and how their town fit together.

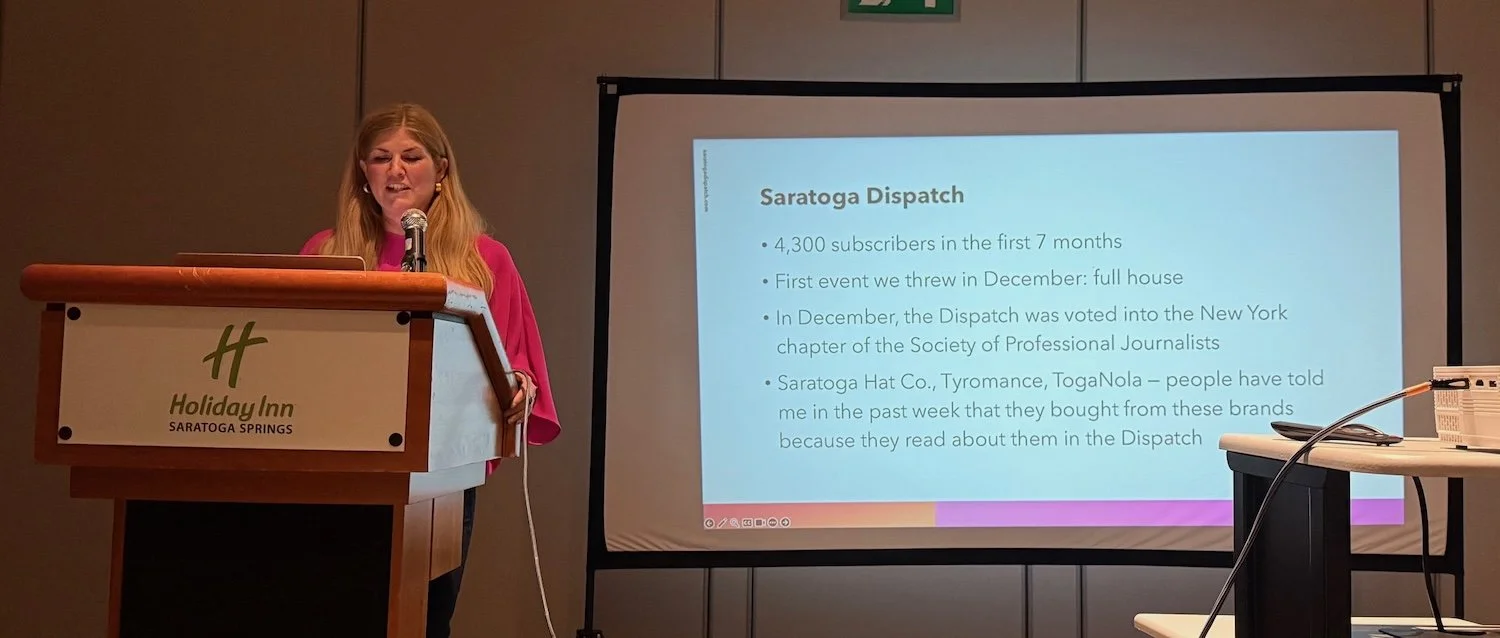

Saratoga Dispatch founder Abby Tegnelia addressed the Torch Club Monday night.

“You knew you were reading the same thing as your neighbor,” Abby Tegnelia, founder of Saratoga Dispatch, told those who gathered Monday at the Saratoga Springs Holiday Inn for the Saratoga Torch Club’s monthly dinner on February 16.

That shared starting point created what Tegnelia calls the “connective tissue” of local life. Papers offered “something for everyone — hard news, international reports, local feel-good stories, columns, comics, movie listings.”

The result was a kind of civic synchronization. When neighbors spoke, they spoke from a common set of facts.

Today, that synchronization is dissolving.

The Collapse of the Old Business Model

Since the early 2000s, thousands of local papers have closed. The causes are familiar but still bracing in their cumulative force. Classified ads once accounted for the majority of newspaper revenue.

“Craigslist came in and took over want ads,” Tegnelia notes. Then came Facebook and Google, offering advertisers unprecedented targeting power. “Advertisers pulled out their newspaper ads because now they can target better online.”

The shift did not stop there. As readers moved to phones, advertisers realized they could reach them in specialized digital environments — movie listings on Fandango, event listings on apps, social updates on feeds.

“Everyone’s on their phones reading, so the print newspaper’s readership started to decline,” Tegnelia says. “So the advertisers who are left are now reaching fewer people, and they want to pay less.”

The economic subsidy that supported local reporting collapsed. Newsrooms shrank. Coverage thinned. The daily habit of reading about one’s own community became optional rather than automatic.

Researchers have since documented the civic cost. Communities without strong local news sources show lower voter turnout, less engagement, and more polarization. Tegnelia points to the simplest indicator of all: “Local news readers are more likely to know their neighbors.”

The disappearance of shared information produces a quiet civic loneliness. People still live near one another, but they inhabit different informational worlds.

And yet Tegnelia does not view this moment as an ending. She sees it as a reset.

The Return of Direct Connection

The newsletter, in her view, represents a structural correction — a return to direct communication between journalist and reader. Unlike social platforms, newsletters are not subject to algorithmic invisibility. They arrive intentionally, in a reader’s inbox, carrying the unmistakable imprint of a human voice.

“The early adapter that convinced me to try this newfangled Substack thing,” she recalls, “was none other than Dan Rather.”

Rather launched his newsletter at the age of 89 and built an audience of hundreds of thousands. For Tegnelia, that example revealed something crucial. The appeal of the format was not demographic; it was relational. Readers did not subscribe to a platform. They subscribed to a person.

In that relationship lies the possibility of rebuilding trust.

Traditional journalism often trained writers to suppress personality in pursuit of objectivity. The newsletter, by contrast, invites presence. Tegnelia believes that voice itself can counter the fatigue many readers feel toward the news. By blending reporting with reflection, seriousness with warmth, writers can build what she calls “a durable bond” with their audience.

It was Dan Rather who inspired Abby to explore Substack.

Journalists as Founders

But the new model requires journalists to adopt a mindset unfamiliar to many in the profession. Tegnelia argues that the future of local journalism depends on entrepreneurial fluency as much as editorial skill.

“For local journalism to remain viable you have to be a creative thinker,” she says. “With independent newsletters, you can bring in revenue any way we want.”

The phrase is less a slogan than a survival principle. Revenue must come from multiple directions: subscriptions, sponsorships, events, merchandise, partnerships. Some newsletters host dinner clubs. Others create local products or develop side ventures built on audience trust.

Tegnelia cites examples ranging from themed Monopoly boards to service businesses launched through newsletter networks.

The underlying lesson is that journalism can no longer depend on a single revenue stream. It must function as a portfolio of relationships.

This shift places journalists in a new role — less like reporters working within institutions and more like founders building them.

The language of startups may seem foreign to traditional newsroom culture, but Tegnelia believes it is precisely what local journalism now requires: agility, experimentation, and a willingness to iterate in public.

Having launched The Dispatch last year Tegnelia now counts 4,300 subscribers.

AI as an Amplifier of Human Journalism

Technology, of course, plays a role in this reinvention, and no discussion of modern media can avoid the question of artificial intelligence. Tegnelia’s view is pragmatic rather than alarmist. She treats AI as a tool — useful for reducing operating costs and handling repetitive tasks — but not as a substitute for human reporting.

She uses AI to summarize long meetings, copyedit text, search records, design presentations, and streamline workflows. These efficiencies allow her to spend more time doing the work that machines cannot replicate: attending events, building relationships, noticing the small signals that reveal what a community cares about.

In this sense, AI becomes an amplifier of human journalism rather than its replacement. It handles the mechanical so the journalist can remain relational.

Rebuilding the Connective Tissue

What emerges from Tegnelia’s approach is a vision of local journalism that is decentralized, personality-driven, and community-supported. The collapse of legacy media structures, she suggests, does not signal the end of local news. It marks the beginning of a new institutional form — one that may ultimately prove more resilient because it rests on direct trust rather than inherited authority.

Saratoga Dispatch, in this light, is not merely a newsletter. It is an experiment in rebuilding civic infrastructure.

For those of us who care about the future of communities like Saratoga, the implications are significant. If Tegnelia is right, the future of local news will not be determined by the revival of old institutions but by the emergence of new ones — smaller, nimbler, more personal, and more intertwined with the daily life of the places they serve.

The connective tissue that once held communities together can be rebuilt if their members join together.

“The sky’s the limit,” she says of the newsletter model. It is an expansive phrase, but it reflects a grounded conviction: that the tools now exist to reconnect communities to themselves.

What remains is the human work of using them well.

And perhaps that is the deeper lesson unfolding here in Saratoga. The future of local journalism will not be decided by technology alone. It will be decided by whether people still believe their stories are worth telling — and whether someone is willing to tell them with enough care that others recognize themselves within them.

If that happens, the rewiring of local news may prove not a loss, but a renewal.